System Logs 101: Ultimate Guide to Mastering System Logs Now

Ever wondered what your computer is secretly recording? System logs hold the answers—revealing everything from errors to user activity. Dive in to unlock their full power.

What Are System Logs and Why They Matter

System logs are detailed records generated by operating systems, applications, and network devices that document events, errors, and activities occurring within a computing environment. These logs serve as a digital diary, capturing timestamps, user actions, system states, and security events. Without them, troubleshooting would be like navigating in the dark.

The Core Definition of System Logs

At their essence, system logs are timestamped entries created by software components to record operational information. They are typically stored in plain text or structured formats like JSON or XML, making them accessible for both human review and automated analysis. According to the US-CERT, logs are foundational to maintaining system integrity and detecting anomalies.

- Generated automatically by OS kernels, services, and daemons

- Include metadata such as timestamps, process IDs, and user IDs

- Stored in standard locations (e.g., /var/log on Linux, Event Viewer on Windows)

Why System Logs Are Critical for IT Operations

System logs are not just technical footprints—they are vital tools for maintaining uptime, diagnosing failures, and ensuring compliance. In enterprise environments, logs help IT teams identify performance bottlenecks before they escalate into outages. For example, a sudden spike in error messages in system logs might indicate failing hardware or misconfigured software.

“Logs are the first line of defense in incident response.” — SANS Institute

Moreover, system logs support accountability by tracking who did what and when. This is especially crucial in regulated industries like finance and healthcare, where audit trails are mandatory under standards such as HIPAA and PCI-DSS.

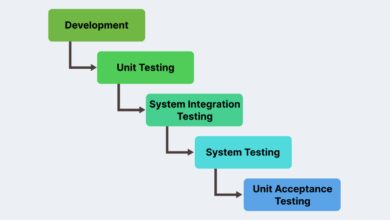

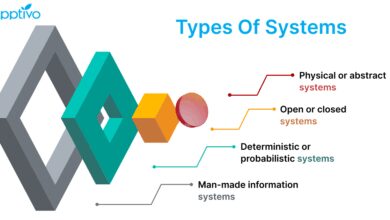

Types of System Logs You Need to Know

Not all system logs are created equal. Different components of a computing environment generate distinct types of logs, each serving a unique purpose. Understanding these categories helps in efficient monitoring and troubleshooting.

Operating System Logs

These are the most fundamental type of system logs, produced by the kernel and core system services. On Linux systems, these include messages from the kernel ring buffer (accessible via dmesg), boot logs, and authentication records. On Windows, the Event Viewer categorizes logs into Application, Security, and System logs.

- Linux: /var/log/syslog, /var/log/auth.log, /var/log/kern.log

- Windows: Application Log, Security Log, Setup Log

- macOS: Unified Logging System (via Console.app)

For deeper insights, refer to the Linux Kernel Documentation, which explains how kernel parameters influence log generation.

Application Logs

Every software application—from web servers like Apache to database engines like MySQL—generates its own logs. These logs capture application-specific events such as login attempts, transaction records, and error stacks. For instance, Apache’s access.log records every HTTP request, while error.log captures failed connections or script errors.

- Web servers: access.log, error.log

- Databases: query logs, slow query logs

- Custom apps: often use logging frameworks like Log4j or Serilog

Properly configured application logs can reduce mean time to resolution (MTTR) during outages by providing precise context about failures.

Security and Audit Logs

Security logs focus on authentication, authorization, and intrusion detection events. They track login successes and failures, privilege escalations, and firewall rule triggers. On Linux, tools like auditd provide granular audit trails, while Windows uses Advanced Audit Policies.

- Failed SSH attempts recorded in /var/log/auth.log

- User account changes logged in Windows Security Event ID 4720

- Firewall drops captured by iptables or Windows Defender Firewall

These logs are indispensable for forensic investigations and compliance reporting. The NIST Special Publication 800-92 emphasizes the importance of centralized logging for security monitoring.

How System Logs Work Behind the Scenes

Understanding the mechanics of how system logs are generated, stored, and managed is essential for effective system administration. This section dives into the architecture and flow of logging processes across different platforms.

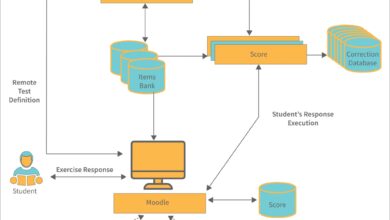

The Logging Architecture: From Event to Entry

When an event occurs—say, a user logs in—the operating system or application triggers a logging function. This function formats the event data (timestamp, user, action, outcome) and sends it to a logging daemon or service. On Unix-like systems, this is often handled by syslog or its modern variants like rsyslog and syslog-ng.

- Event occurs (e.g., service starts)

- Logging API (e.g., syslog()) is called

- Message routed to appropriate log file based on facility and severity

The syslog protocol uses facilities (e.g., auth, kern, mail) and severity levels (0=emergency to 7=debug) to classify messages. This structured approach enables filtering and prioritization.

Log Rotation and Management

Without proper management, system logs can quickly consume disk space. Log rotation solves this by periodically archiving old logs and compressing them. Tools like logrotate (Linux) and built-in Windows policies automate this process.

- Rotate logs daily, weekly, or when they reach a size threshold

- Compress old logs using gzip or bzip2

- Delete logs after a retention period (e.g., 30–90 days)

Improper log rotation can lead to disk full errors, causing system instability. Always test rotation scripts and monitor disk usage proactively.

Top Tools for Monitoring and Analyzing System Logs

Raw log files are overwhelming without the right tools. Modern log management solutions help collect, parse, visualize, and alert on system logs at scale.

Open-Source Log Management Tools

For organizations seeking cost-effective solutions, open-source tools offer powerful capabilities. The ELK Stack (Elasticsearch, Logstash, Kibana) is one of the most popular choices.

- Elasticsearch: Stores and indexes logs for fast search

- Logstash: Ingests, parses, and transforms log data

- Kibana: Provides dashboards and visualizations

Another notable tool is Graylog, which combines log collection, indexing, and alerting in a single platform. Both tools support parsing system logs from multiple sources and can scale across distributed environments.

Commercial Log Analytics Platforms

Enterprises often opt for commercial solutions like Splunk, Datadog, or Sumo Logic. These platforms offer advanced features such as machine learning-based anomaly detection, real-time alerting, and seamless cloud integration.

- Splunk: Industry leader with powerful search processing language (SPL)

- Datadog: Integrates logs with metrics and traces for full observability

- Sumo Logic: Cloud-native platform with automated log parsing

While these tools come with licensing costs, they significantly reduce the operational burden of managing system logs at scale.

Command-Line Tools for Quick Log Inspection

For quick troubleshooting, command-line utilities remain indispensable. Tools like grep, tail, awk, and journalctl allow administrators to filter and analyze logs directly on the server.

tail -f /var/log/syslog: Monitor logs in real timegrep "ERROR" /var/log/apache2/error.log: Find specific error messagesjournalctl -u nginx.service: View logs for a specific systemd service

Mastering these commands is essential for any system administrator dealing with system logs.

Best Practices for Managing System Logs

Effective log management goes beyond just collecting data. It involves strategic planning, configuration, and ongoing maintenance to ensure logs are useful, secure, and compliant.

Centralize Your Logs

Storing logs on individual servers makes analysis difficult and increases the risk of data loss during failures. Centralized logging—sending all system logs to a dedicated server or cloud platform—improves visibility and security.

- Use syslog servers (e.g., rsyslog, syslog-ng) to aggregate logs

- Forward logs to SIEM systems like Splunk or QRadar

- Ensure network reliability and encryption (TLS) for log transmission

Centralization enables cross-system correlation, helping detect attacks that span multiple hosts.

Standardize Log Formats

Inconsistent log formats make parsing and analysis challenging. Adopting standardized formats like JSON or using structured logging libraries ensures uniformity.

- Use tools like Fluentd or Logstash to normalize log formats

- Enforce structured logging in custom applications

- Include essential fields: timestamp, log level, source, message

Structured logs are easier to query and integrate with analytics platforms.

Secure and Retain Logs Properly

System logs often contain sensitive information, including IP addresses, usernames, and error details. Securing them is critical to prevent tampering and unauthorized access.

- Set strict file permissions (e.g., 600 for sensitive logs)

- Encrypt logs in transit and at rest

- Define retention policies based on compliance requirements

The ISO/IEC 27001 standard recommends protecting log data as part of an organization’s information security management system.

Common Challenges in System Log Management

Despite their importance, managing system logs comes with several challenges that can undermine their effectiveness if not addressed.

Log Volume and Noise

Modern systems generate massive amounts of log data. A single web server can produce thousands of entries per minute, making it hard to spot critical issues amidst the noise.

- Implement log filtering to suppress low-severity messages

- Use sampling for high-frequency events

- Leverage AI-driven tools to detect anomalies

Without proper filtering, important alerts can be buried under irrelevant entries.

Time Synchronization Issues

Accurate timestamps are crucial for correlating events across systems. If servers have unsynchronized clocks, log analysis becomes unreliable.

- Use NTP (Network Time Protocol) to synchronize time across all devices

- Monitor NTP status regularly

- Ensure virtual machines sync with host clocks

A time drift of even a few seconds can mislead incident investigations.

Log Integrity and Tampering Risks

Attackers often delete or alter system logs to cover their tracks. Ensuring log integrity is vital for forensic accuracy.

- Send logs to immutable storage or write-once media

- Use cryptographic hashing to detect modifications

- Enable remote logging so attackers can’t erase local logs

As noted by the MITRE ATT&CK framework, log tampering is a common post-exploitation tactic (Tactic: TA0005).

Advanced Use Cases of System Logs

Beyond troubleshooting, system logs enable sophisticated use cases in security, compliance, and performance optimization.

Threat Detection and Incident Response

System logs are a goldmine for identifying malicious activity. Unusual login times, repeated failed authentications, or unexpected process executions can signal a breach.

- Set up alerts for brute-force attack patterns

- Correlate firewall and authentication logs to detect lateral movement

- Use SIEM rules to trigger incident response workflows

For example, detecting Event ID 4625 (failed logon) followed by 4670 (permissions change) in Windows logs could indicate privilege escalation.

Compliance and Audit Readiness

Regulatory frameworks require organizations to maintain audit trails. System logs provide the evidence needed for compliance audits.

- HIPAA: Logs must track access to protected health information

- PCI-DSS: Requires logging of all access to cardholder data

- GDPR: Logs support data subject access requests and breach notifications

Regular log reviews and retention audits ensure readiness for regulatory scrutiny.

Performance Monitoring and Optimization

System logs can reveal performance bottlenecks. Slow database queries, high memory usage, or disk I/O delays often leave traces in logs.

- Analyze application logs for slow response times

- Monitor system logs for OOM (Out of Memory) killer events

- Track service restarts and crash patterns

By correlating logs with metrics, teams can proactively optimize system performance.

Future Trends in System Logging

The field of system logging is evolving rapidly, driven by cloud computing, AI, and the need for real-time insights.

Cloud-Native Logging Architectures

With the rise of microservices and containerization, traditional file-based logging is giving way to cloud-native approaches. Platforms like Kubernetes use sidecar containers and logging operators to stream logs to centralized backends.

- Fluent Bit and Promtail for lightweight log collection

- OpenTelemetry for unified telemetry (logs, metrics, traces)

- Serverless logging in AWS CloudWatch and Azure Monitor

These architectures support dynamic, ephemeral environments where logs must be collected before containers disappear.

AI-Powered Log Analysis

Artificial intelligence is transforming log analysis by automating pattern recognition and anomaly detection. Machine learning models can learn normal behavior and flag deviations without predefined rules.

- Auto-clustering of similar log messages

- Predictive alerting based on historical trends

- Natural language processing for log summarization

Tools like Google Cloud’s Operations Suite and IBM Watson AIOps are pioneering this space.

The Rise of Observability Platforms

Modern IT operations are shifting from reactive logging to proactive observability. Observability platforms combine logs, metrics, and traces to provide a holistic view of system health.

- Unified interfaces for debugging across layers

- Contextual linking between logs and metrics

- Root cause analysis powered by correlation engines

This shift enables faster resolution of complex, distributed system issues.

What are system logs used for?

System logs are used for troubleshooting, security monitoring, performance analysis, compliance auditing, and forensic investigations. They provide a chronological record of events that helps administrators understand system behavior and respond to incidents.

Where are system logs stored on Linux?

On Linux, system logs are typically stored in the /var/log directory. Key files include /var/log/syslog (general system messages), /var/log/auth.log (authentication logs), and /var/log/kern.log (kernel messages). Systemd-based systems also use journalctl to access binary logs.

How can I view system logs on Windows?

You can view system logs on Windows using the Event Viewer (eventvwr.msc). Navigate to Windows Logs > System to see system-level events, or Application to view app-specific logs. Security logs require administrative privileges.

How long should system logs be retained?

Retention periods vary by industry and regulation. General best practices suggest keeping logs for 30 to 90 days. However, compliance standards like PCI-DSS require at least one year of retention for certain logs.

Can system logs be forged or deleted?

Yes, attackers can delete or alter local system logs if they gain administrative access. To prevent this, logs should be sent to a secure, centralized, and immutable logging server that the attacker cannot reach.

System logs are far more than just technical records—they are the backbone of system reliability, security, and compliance. From diagnosing crashes to detecting cyberattacks, their value is undeniable. By centralizing, standardizing, and securing your logs, you transform raw data into actionable intelligence. As technology evolves, so too will the tools and practices around system logs, but their fundamental role will remain unchanged: to tell the truth about what happens inside your systems.

Further Reading: